Definition

Argumentum ad Ignorantiam (Because everything is more credible when said in Latin).

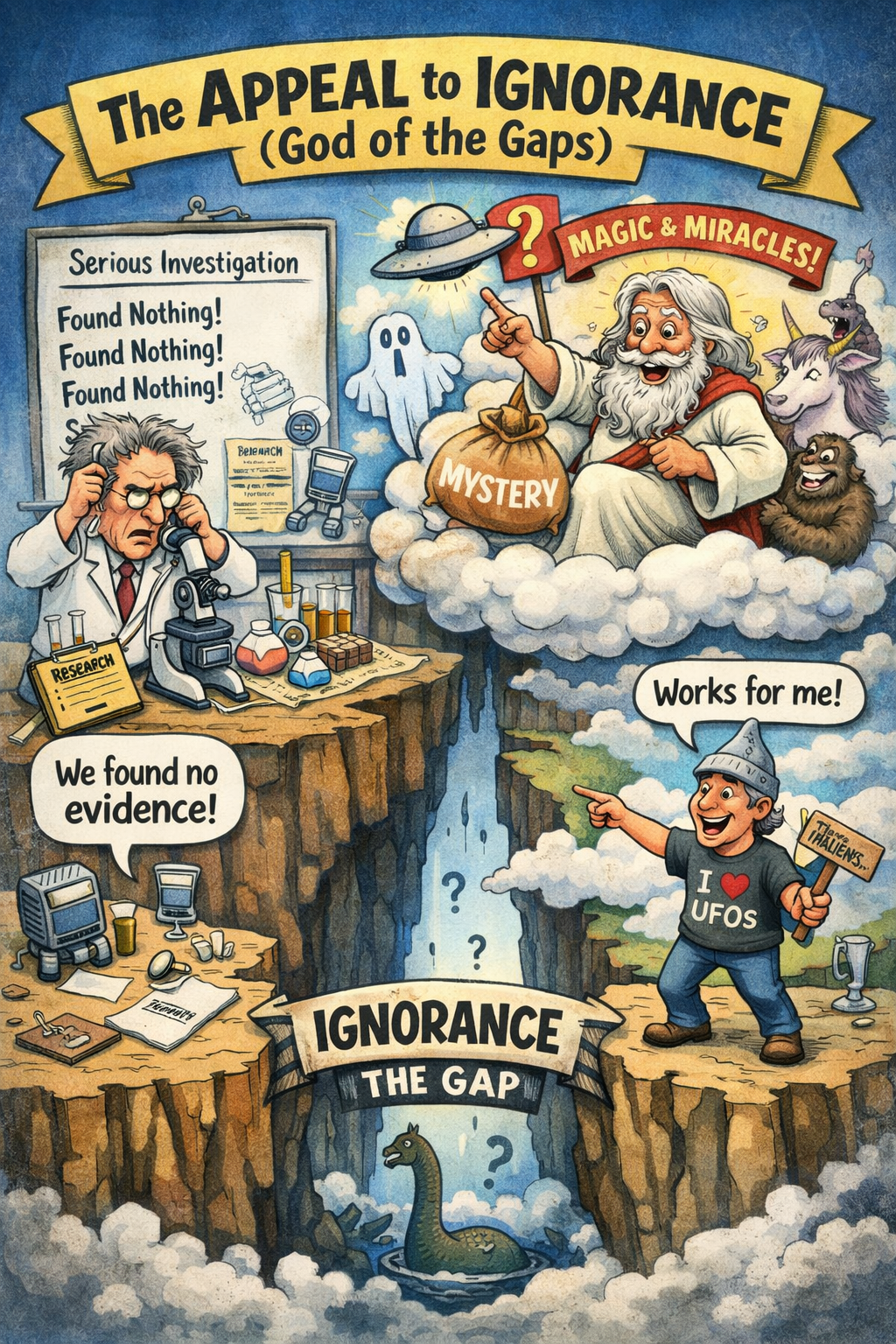

An appeal to ignorance is when we draw a conclusion from the mere fact that something hasn’t been proven when no meaningful search, test, or investigation has actually been conducted.

It occurs when someone draws a conclusion, positive or negative, from a gap in knowledge that hasn’t been addressed by actual, relevant, inquiry. The speaker treats raw, uninvestigated ignorance as evidence of ‘something’.

The core error looks like this:

“No one has proven X is false [and no one has seriously tried]. Therefore, X is true [or functionally equivalent to an alternative].”

or

“No one has proven X is true [and no one has seriously tried]. Therefore, X is false.”

or

“I personally don’t know of any evidence for X [and I haven’t looked or had the ability to find evidence]. Therefore, there is no evidence.”

The problem in every case is the bracketed part — the absence of genuine inquiry.

Absence of evidence IS valid as evidence when:

- A thorough investigation was conducted in a domain where evidence would be expected to appear if the claim were true. You test a well for contamination using proper methods and find none that is a meaningful finding.

- The claim predicts observable consequences that should be detectable, and a competent search for those consequences comes up empty. If someone claims there’s a gas leak in your house and a calibrated detector reads zero, the absence of a reading is real information.

When absence of evidence is NOT valid evidence (the actual fallacy):

- No investigation has been conducted at all. The speaker is simply unaware of any evidence and treats that personal ignorance as a conclusion.

- The investigation was inadequate: too narrow, too shallow, or looking in the wrong place. Finding nothing under those conditions tells you very little.

- The claim is structured so that evidence wouldn’t be visible regardless of whether the claim is true or false. You can’t draw conclusions from failing to find something that was never findable. (See Unfalsifiable Conclusions once its written).

- The speaker’s personal lack of knowledge is treated as a universal limit. “I’ve never heard of it” becomes “it doesn’t exist.”

Examples

“Nobody has ever proven that my lucky socks don’t help me win. So they must work.”

What’s wrong: No one has tested the claim. It should be obvious that isn’t evidence of anything.

“I’ve never heard of a successful case of that treatment working. So it doesn’t work.”

What’s wrong: Unless the speaker has a certain amount of expertise personal awareness is not a substitute for a survey of the evidence. They may not have looked, may not have access to the relevant literature, may not understand what they have seen or may simply have missed it. Treating “I don’t know about it” as “it doesn’t exist” is confusing the map with the territory.

When politicians say, “There was no evidence of fraud in the election.”

This may be honest or it may be complete fallacy. The meaning changes 100% based on contextual facts.

If a thorough, multi-method audit was conducted with proper access to ballots, machines, and records, and it was done by reliable parties with transparency and oversight, the absence of findings is meaningful evidence. It is how we know that the US 2020 election, or at least the counting of the votes, was one of the most honest elections in history.

If “no evidence” means “we didn’t look” or “we did a cursory review with limited scope” it tells you almost nothing and presenting it as a clean finding is fundamentally dishonest.

When companies say, “There’s no evidence this chemical is harmful to humans.”

It can mean:

(a) the chemical was rigorously tested and no harm was detected — a genuine finding, or

(b) no adequate testing has ever been done — raw ignorance.

Companies routinely use the language of (a) when the reality is (b). The sentence sounds like a safety finding, but it may be an admission that nobody has looked. The Appeal to Ignorance here isn’t the absence of evidence — it’s the fraudulent presentation of uninvestigated ignorance as a researched conclusion.

And the other side of the coin, the favourite argument of the pseudo-skeptic – “There’s no peer-reviewed, double blind study proving that, so it’s not real.”

What’s happening: If the topic has been studied and no supporting evidence was found, this is a reasonable (though not airtight) position. But if the topic simply hasn’t attracted research funding, hasn’t been deemed interesting by the academic establishment, or exists in a domain where peer review isn’t the norm and/or blind testing isn’t feasible, then “no peer-reviewed study” may reflects anything from, the priorities of research institutions to the nature of the domain. The fallacy here is treating the absence of a particular type of investigation as equivalent to a negative finding from that investigation.

Common Forms of the Appeal to Ignorance

Form 1: “Not disproven, therefore true”

The speaker makes a claim and, instead of supporting it, challenges others to disprove it. When they can’t, often because the claim is vacuous, poorly defined or unfalsifiable, or because disproving it would require impractical effort vs winning the argument, the speaker treats the claim as validated.

- “You can’t prove I didn’t see what I saw.”

- “Nobody has been able to explain those lights. So they must have been aliens.”

Form 2: “Not proven, therefore false”

The speaker dismisses a claim solely because supporting evidence hasn’t been presented without considering whether anyone has actually tried to gather such evidence.

- “There’s no study proving that, so I reject it.”

- “You can’t show me a single documented case.”

- “No one has demonstrated that to my satisfaction.”

Form 3: “I don’t know it, therefore nobody knows it”

The speaker treats the limits of their own knowledge as the limits of knowledge itself. This is the most common everyday form and the one people are least likely to recognize in themselves. The issue is confusing one’s personal ignorance with the knowledge level of others.

- “I’ve never experienced discrimination, so I think it’s overstated.”

- “I don’t know anyone who’s had that side effect.”

- “I’ve never heard of that happening.”

Form 4: “No complaint, therefore no problem”

The absence of formal objection is treated as evidence that everything is satisfactory — ignoring every reason people might choose not to speak up.

- “We’ve had zero complaints about this policy.”

- “If it were really a problem, someone would have said something.”

- “No one has raised any concerns.”

Complaint rates reflect reporting environments. Low complaints from a low trust system where complaining is perceived to have great costs is not evidence of success.

Quick Checklist

When you encounter a claim built on the absence of evidence, ask:

- Was there actually an investigation? “No evidence” after a thorough, competent search is meaningful. “No evidence” when nobody has looked is just ignorance wearing a lab coat. Find out which one you’re dealing with.

- Was the search adequate to the claim? Even when an investigation occurred, its design matters. A search in the wrong place, at the wrong scale, or with the wrong instruments can miss what’s there. The absence of a finding is only as strong as the method that produced it.

- Could the evidence have been found if the claim were true? If the claim is structured so that no evidence would be visible regardless of whether it’s true — the absence of evidence is uninformative. You’re looking into a void, not at a result.

- Is someone’s personal ignorance being presented as a universal fact? “I’ve never seen it” is a statement about one person’s experience. It becomes a fallacy when it’s offered as “it doesn’t happen.” Watch for the moment when subjective limits get stated as objective conclusions.

- Who benefits from the gap? When someone has a financial, political, or personal stake in a question remaining uninvestigated, their use of “no evidence” language warrants particular scrutiny. Sometimes the absence of evidence is an engineered outcome, not a natural one.

- Is absence of complaint being treated as presence of satisfaction? In any environment where raising concerns carries risk — professional, social, familial — silence is not data. It’s an absence of data, and an honest assessment acknowledges that.

The Honest Alternative

The corrective is not to dismiss the evidential value of absence — it is to be precise about what kind of absence you’re dealing with.

- Instead of “no one has proven X, so it’s false,” say: “X hasn’t been established yet. Has it been properly investigated? If not, we genuinely don’t know.”

- Instead of “you can’t disprove X, so it’s true,” say: “The claim hasn’t been ruled out, but the fact that no one has disproved it only matters if disproof was genuinely possible and attempted.”

- Instead of “I’ve never seen it, so it doesn’t happen,” say: “I haven’t personally encountered it. That’s one data point, and I should consider what falls outside my line of sight.”

- Instead of “no one has complained,” say: “We haven’t received complaints. But before we treat that as a finding, we should ask whether people felt they could complain.”

- Instead of “there’s no evidence of harm,” say: “Has this been tested for harm, or has it simply not been tested? Those are very different statements.”

Intellectual honesty begins with distinguishing between “we looked and found nothing” and “we never looked.” The Appeal to Ignorance is the refusal to make that distinction.